- Home

- Magdalen Dugan

Lift My Eyes Page 2

Lift My Eyes Read online

Page 2

I wish I could have said good-bye to him. I would have kissed his cheek the way I used to when he was alive, when his whiskers tickled my lips and he smelled like soap and tobacco. Some of his family has gone up to kiss him. I am afraid to kiss him now.

Mr. Carter says Tod did not have to fight because he was a quartermaster. That’s a soldier who takes care of the other soldiers. Tod did not have to fight, but I know he wanted to help; he always wanted to help. He rode into the battle crying out, “Follow me, boys. I’m almost home.” But a bullet hit him as he was almost at his home, and he couldn’t walk by himself anymore. The blue soldiers killed him and I will not forgive them.

Why can I not cry? Mrs. Carter is crying so much they have to take her out for a while. I just keep thinking it is so strange to look at him lying there, when only a few days ago he was telling me I was his sweetheart and swinging me through the air. I guess I did not really believe that he would wait for me and marry me because he is—he was—a big man and I am a little girl, but I did know he liked me and I liked him. Now he is gone, and only this too-still body is left.

Everyone has brought what food they have left from the raiding of the blue soldiers, and after we pray for Tod to be at peace we eat together, but no one talks much. No one but my family seems to notice that I cannot speak, not at all. We are all together in the same bad dream.

*****

JANUARY 1, 1923

Tata, Hungary

I have drawn as close to the fire as I can without scorching my skirts. Life here in Tata is difficult at any time, but in winter it is nearly impossible. Though wrapped in wool from the outside in, even to my woolen stockings, I cannot fend off the damp cold. My muscles are tightened with it and will not let go. The outdoor thermometer has read below zero for more than a month, and the constantly falling wet snow soon hardens to ice, sealing us inside this house like insects in amber. We spend most of our day in this parlor where we can afford to keep a fire burning. Several times a day I venture to the kitchen to make tea or prepare some soup. At night we return to the cocoon of our bedroom and the oblivion of sleep. So it has been, day after day, for each of the eight winters we have lived here.

My husband Ferenc reaches to take my free hand. Though he is aging as I am, and though his country is crumbling around him, he is still every inch the nobleman—sitting erect in his wing chair, pipe in hand, perusing the newspaper. In the ten years we have been married, his hair, which he wears long to his jawline, has taken on a hue of vigorous iron grey. As he turns to smile at me, the tanned skin of his face creases like fine leather and his hand, as he holds mine, has the supple softness of my Florentine kidskin gloves. My hand rests in his as if in a glove, snugly, comfortingly.

Ferenc often teases me about having to sit to my left if he hopes to capture my hand, since my right hand is always busy sketching or writing. Although I do not have great energy for either today, the potential this new year offers compels me to try. I will not paint today, though. I am not ready. I need to consider how to make an end of what has been so that I can begin again. The cycle of life requires it.

The Great War has been over for more than two years, but I have not been able to make an end of it. A million of this country’s soldiers are dead, and many more are missing in action. In Tata, scarcely a household has escaped tragedy. Most of those who have returned are missing parts—legs, arms, minds, the will to live. This small community has had its life sucked from it, and it is no doubt the same everywhere.

For nearly eight years we have been hungry—some dangerously so, some, like me, only annoyingly so. I eat enough to sustain myself—bread, soup, an egg when one is available. Since the blockade of food has been lifted and the soldiers have come home to farm again we have better food with more variety, but over the past years I have learned to eat little. I must not complain. Often, as I serve soup to the townspeople, I look into the wan faces and sunken eyes of those far hungrier than I.

The truth is that I am ashamed to be so miserable. My husband is alive, whole, and at my side. I am not starving; I am not without shelter. I am free to paint as much as strength allows. But I am still very, very angry. What right did they have to set the world to killing one another?

I am shivering now, and must wrap the blankets more closely around my legs and shoulders. As he reads the newspaper, Ferenc once in a while comments aloud on world events, which, for some reason, still interest him. The empire that was once his heritage is splintered into more than a dozen pieces, which still, postwar, are being invaded by enemies and infiltrated by agitators wanting revolution. Evidently Russia has formed a “Soviet Union,” and what that will mean to us here in what is left of Hungary is something he tries to imagine.

I do not trust any of them—the heads of state, the princes, the sons of men. They have taken nearly everything of value, though they cannot completely take us from each other as long as we can remember.

And what is there to do today in Tata, Hungary, at sixty-five years old, in the depth of winter, in the depth of exile, except to remember? Moments of my life are flashing through my thoughts like the images of a kaleidoscope—light, patterns, colors—a bright, fragmented panorama.

*****

NOVEMBER 29, 1864

(FOUR DAYS BEFORE THE BATTLE)

Franklin, Tennessee

Running down the stairs, I pass my palm along the cool smoothness of the bannister Papa has made. I swing around the corner and into the dining room, which holds even more wonders than I have been imagining all this week as I have waited for today. Mama and Amelia have baked me a cake, and displayed it on a tall glass stand. It is decorated with white butter frosting and clusters of red gooseberries. I know that inside that frosting I will find pieces of crunchy pecan and soft, sweet apple. More apples decorate the table, along with a pitcher brimming with Ute’s creamy milk.

The whole family is here for my sixth birthday party. Papa sits at the head of the table, handsome in a dark-blue suit and a light-blue shirt that make his eyes look even bluer than usual. Mama is serving, standing tall over the table. She is a big, strong woman, almost as tall as Papa, with deep-set, golden-brown eyes. She has piled her curly brown hair on top of her head, and pulled some down into long tendrils that fall over her shoulders. When she is working indoors, she smells of bread dough and washing soap and lavender, but when she is working outdoors she smells of garden loam and pasture grass.

My brother Joseph, who has finished high school and gone to work in Nashville, has returned just for my party, and Tod Carter, our neighbors’ son, has taken leave from the Confederate Army to visit his family and Joseph. Tod is a Confederate soldier, but he is not dressed in his gray uniform today. He says he can stay only a few hours, because the Yankees are occupying our town and may cause him trouble if they find him. He always talks about how he is loyal to the Confederacy to the death, how he would do anything to protect his home and his way of life. Today he is arguing with Joseph for refusing to take a side in the war.

“Look, Lotz, I know you are not a coward, but it has to look that way to people who don’t know you.”

“People can think what they like. My father does not take a side, and it is clear that he is not a coward,” Joseph answers.

“He certainly is not. My apologies, Mr. Lotz. I would never imply such a thing. But, Joe, even though your family is Bavarian, you grew up here. You are a Tennessean.”

“The United States is my country, not Tennessee or the North or the South but the whole country. This is not my battle you all are fighting.”

Then Tod pretends to be mad. He punches Joseph in the arm and wrestles with him a little before they slap each other on the back and drink some punch. Joseph and Tod grew up together and are almost brothers.

Though of course he has come to see his friend, Tod insists that he is here particularly to see me because I am his girl. He has brought me a tiny toy wagon carved of wood, drawn by a perfect wooden ox with delicate horns curving from its

bowed head.

“Did you carve this, Tod?” I ask, cradling his gift in my cupped palms.

“I sure did. I made it for my girl. You are still my girl, aren’t you, Tillie? Or have you gotten too old to be interested in a young fella like me?”

I laugh, and everyone laughs, and Tod lifts me by the shoulders and spins me in a circle so that the skirt of my blue wool dress bells out around me.

“This may be Tennessee, but you look just like a Virginia bluebell, Miss Tillie,” he says, returning me to my feet and bowing.

Joseph has also made a gift, a braided leather leash, to lead my pet calf Mattie. But the best gift of all comes from Papa and Mama—a tablet of paper and a set of Faber pencils.

“You have done well with your stick drawings, my Tillie,” Papa says. “It is time now to draw some pictures you can keep.”

He lays his hand on my head as if blessing me, and his hand is warm and kind. Mama’s eyes smile in the silent way she has, and I know she is proud of me. I get up from the table to hug first Papa, then Mama. Paul and I exchange excited glances, and he mouths the words, “Tomorrow morning.” My brother Paul is nine, just old enough to protect and help me. He is my best friend. We are always drawing together, and now, when we have perfected a stick drawing, we will be able to transfer it to the precious new paper. I know what the subject of this first drawing will be—Mattie, my pet calf.

*****

APRIL 1864

(SEVEN MONTHS EARLIER)

Franklin, Tennessee

“Go ahead, Matilda. Don’t be shy,” my brother Joseph urges me, patting my shoulder.

Joseph is my hero, nearly a man already, just about to finish high school with honors and go out into the world.

“This is your calf, Matilda. Papa said she could be. So you have to name her,” he insists.

We have watched as our milk cow Ute has birthed a little wet lump of pink flesh that looks barely alive. Besides Joseph, my big sister Amelia is here, and my closest brother Paul. Our baby brother Augustus, “Gus,” is only three and has not been admitted to this important event. During the birth, Ute bellowed fiercely for the longest time, and finally the small, sweet creature dropped. We have stayed here while the pink lump found her feet and teetered onto her wobbly legs to drink from Ute’s teat.

At five years old, I feel very grown up to be allowed to watch this wonder, and especially to know that Ute’s calf will be my own pet. But what special name can I give her?

“Can I call her Tillie, like Papa calls me?”

“It isn’t proper to call an animal after a person,” Amelia says.

Amelia is already seventeen and she is always saying things like this, much more often than Mama does. I want to tell her that she is not my mother, but I resist. The occasion is too special for a fight with Amelia. Besides, she can be kind sometimes, and when she plays the piano I could listen to her all day.

But I am baffled. I don’t know many names that aren’t names of people or towns or something I couldn’t call a calf.

“W-e-l-l-l,” says Joseph, never at a loss, “how about if we call her “Mattie”? That’s the first part of your name, but no one calls you that, so Amelia can’t object.”

I throw my arms around Joseph’s leg, and then scramble between the fence slats to pet my new calf and lay my cheek against her damp, warm side. “Hello, Mattie,” I whisper into her moist ear. “You and I are going to be friends.”

And we are. All through that last spring before the battle, Mattie and I run through the pastures together. Her rough tongue tickles my palm as I feed her with the greenest, most tender new grass. I like to roll down the grassy hill above the pasture where she grazes, and surprise her with a hug. Sometimes I climb up on her back and ride her through the pasture, until Amelia calls to me to get down before I break my neck. Most of the time I obey, though it doesn’t seem so far to fall.

*****

NOVEMBER 30, 1864

(SEVEN MONTHS LATER, THE DAY OF THE BATTLE)

Franklin, Tennessee

I wake at sunrise and run to the window to take in the brilliant colors. I cannot wait to draw my first picture on paper, one I will be able to keep. It will be of my Mattie.

I dress quickly, shivering in the cold air. Grabbing my new pencils and tablet, I run down the stairs and out the back door. Mattie is standing in the pasture, nibbling grass, but when she sees me, she comes right up to the fence to lick my hands and face.

I begin to sketch her, first using a stick to draw in the bare earth along the fence line, the way I have always done with Paul. Her silky skin is white with patches of black; her deep, peaceful brown eyes are looking into mine. I try many sketches in the earth, and when Paul joins me, he corrects a line here, a curve there, until he finally agrees that I am ready to use the pencils and paper. But now I must learn an early lesson about the limits and challenges of each different medium, because pencil and paper work very differently from stick and earth. Especially, I must begin to learn about shading, showing light and shadow in ways impossible with the earthen sketches but necessary on paper. I must erase and begin again many times. After about two hours, Paul and I return to the house, hungry and a little frustrated.

That day I do not finish my first real drawing.

As we are eating our lunch, we hear something strange, look at each other, and jump up in alarm. From the Granny White turnpike, and eventually right in front of our house, comes a noise such as I have never heard before, as if all the people in the huge city of Nashville were in one small spot, talking all at once. We run out to the front yard, and I cannot believe my eyes—as far as I can see in both directions, the Pike is filled with blue uniforms.

These blue soldiers themselves are not a strange sight to me; some have been here since spring, though Papa and Mama always say they have no right to be here, no right to make the demands they do. I know that they killed our babies, and I already hate them, but up until now there have been only a few. This appearance today is something else entirely—a powerful river of blue that I know does not mean us any good. My stomach feels sick and I think I might lose my lunch. And then, some of them walk right up to our porch and knock on the door. Paul and I crouch down at the side of the house, where we can hear them but they cannot see us. Papa answers the door.

“Are you the owner of this property?” a Yankee soldier demands of Papa.

“I am. I am Johann Albert Lotz, and this is my house.”

“By order of Major General Schofield, my men are occupying your land.”

“For what possible purpose?”

“We need a base and provisions. We will also need wood for a battlement.”

“But my family—”

“We will not harm your family, Mr. Lotz.”

They talk some more, and Papa sounds very upset, but in the end the blue uniforms begin to swarm over our yard. Papa calls us all inside, and I watch from the back windows as they tear down our barn, our stable, our kitchen house, and all the other buildings except our house itself. They even tear down Papa’s woodworking shop, though Papa pleads with them to spare it for our livelihood. Then to all our horror, they cut down our trees, every one of them—the cedar that smelled like perfume every time Papa cut branches to make chests, the dogwood that burst into white blooms in spring, even the huge old oak we played under in the summertime, where Paul and I would lean against the trunk as thick as a wall and look at picture books, all fallen to the ground and hacked to pieces so that the land is not our yard any longer.

Worse than all of this, with guns and swords and bayonets they kill our animals—our eight hogs and our twelve sheep and our whole flock of chickens. The grass is red with blood. The death sounds of that slaughter are not like those of hog-killing in the fall, when Papa takes an animal or two that we will need for winter meat. This is an hour of total devastation, with scarcely a creature left standing. While Amelia and I hold each other and cry, they even kill gentle, good Ute, who does not even know to

resist, but stands there patiently as they shoot her in the head.

Papa has told us we must stay inside, but when they shoot Ute, I know that the unthinkable could happen, and I run out the back door before anyone can stop me, run as fast as I can toward the pasture where I left little Mattie only a few hours before. As accustomed as I am to obeying Mama, when she calls after me, I do not even turn around.

But before I reach the pasture, I can see that it is too late. Mattie is lying on her side, bleeding from her head. I run to cradle her poor head in my lap. She is lowing miserably, her eyes seeming to search mine for an answer to why this is happening. I stroke her sides. Her blood reddens my hands and arms, soaks into my skirt. We sit like this for a very long time until she goes silent, and then limp.

It is as if I were watching all of this, and not experiencing it myself. A girl, all covered with blood, is holding in her lap a dead calf, her pet, her special friend. It is sad.

A blue uniform with a face watches me, approaches me, and begins to speak. At first I do not hear what he is saying, though his mouth is moving. Eventually I register bits and pieces of his words.

“Sorry, little girl… I did not mean to...got carried away…tired and hungry…following orders…daughter about your age…”

To my surprise and horror, this hand that has killed Mattie is reaching toward me, is about to touch me. I jump to my feet, wrenched from sorrow by another feeling I do not understand, one that seizes me strongly, shakes my body.

“Do not touch me! I hate you. You are bad. You kill everything. You steal and destroy everything. Go away! Go away right now and leave us alone!”

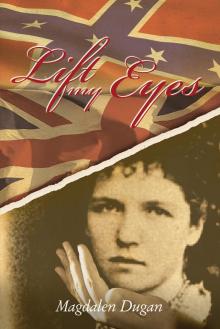

Lift My Eyes

Lift My Eyes