- Home

- Magdalen Dugan

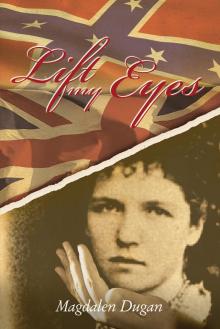

Lift My Eyes

Lift My Eyes Read online

LIFT MY EYES

LIFT MY EYES

Magdalen Dugan

© 2019 Magdalen Dugan

Lift My Eyes

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or other—except for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Elm Hill, an imprint of Thomas Nelson. Elm Hill and Thomas Nelson are registered trademarks of HarperCollins Christian Publishing, Inc.

Elm Hill titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fund-raising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected].

Publisher’s Note: This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. All characters are fictional, and any similarity to people living or dead is purely coincidental.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018966236

ISBN 978-1-400308606 (Paperback)

ISBN 978-1-400308613 (Hardbound)

ISBN 978-1-400308620 (eBook)

Information about External Hyperlinks in this ebook

Please note that footnotes in this ebook may contain hyperlinks to external websites as part of bibliographic citations. These hyperlinks have not been activated by the publisher, who cannot verify the accuracy of these links beyond the date of publication.

For David , Zoe, and Peter,

the best of editors

TABLE OF CONTENTS

January 1, 1923

June 1864

(Sixty-one years earlier)

January 1, 1923

December 3, 1864

(Sixty years earlier)

January 1, 1923

November 29, 1864

(Four days before the battle)

April 1864

(Seven months earlier)

November 30, 1864

(Seven months later, the day of the battle)

November 30, 1864

(Later that day, around dusk)

November 30, 1864

(The night of that same day)

December 1, 1864

(The next day)

December 1864

(The next week)

December 1864

(About a week later)

December 24, 1864

(Another week later)

December 24, 1913

(Forty-nine years later)

December 24, 1915

(Two years later)

December 24, 1915

(The evening of that same day)

December 25, 1864

(Forty-one years earlier, the Christmas after the battle)

January 1865

(The next month)

April 16, 1865

(Three months later)

November 16, 1898

(Thirty-three years later)

October 1887

(Eleven years earlier)

May 1865

(Twenty-two years earlier)

November 29, 1865

(Six months later)

July 1869

(Four years later)

Late July 1869

(About two weeks later)

August 1869

(Two days later)

Late August 1869

(Two weeks later)

September 1869

(Two weeks later)

February 1, 1870

(A little more than four months later)

February 1870

(Later that same month)

October 1869

(About four months earlier)

September 1894

(Twenty-five years later)

October 1913

(Nineteen years later)

March 1870

(Forty-three years earlier)

August 14, 1880

(Ten years later)

October 1883

(Three years later)

April 1889

(Six years later)

December 1894

(Five years later)

September 1890

(Four years earlier)

September 1880

(Ten years earlier)

September 1874

(Six years earlier)

Late February 1870

(Four years earlier)

April 17, 1870

(Two months later)

August 1870

(Four months later)

November 1870

(Three months later)

August 1872

(Two years later)

December 28, 1877

(Five years later)

October 21, 1897

(Twenty years later)

October 28, 1897

(The next week)

April 1900

(Two and a half years later)

September 1900

(Five months later)

December 10, 1900

(Three months later)

April 1905

(Four and a half years later)

November 11, 1905

(Six months later)

April 1910

(Four and a half years later)

April 1910

(The following week)

June 1911

(One year later)

August 1913

(Two years later)

September 8, 1913

(One month later)

June 30, 1914

(Nine months later)

July 1914

(Two weeks later)

June 1883

(Thirty-one years earlier)

January 1885

(Two years later)

January 1885

(Two years later)

Fall, 1872

(Twenty-seven years earlier)

Spring, 1873

(About six months later)

Summer, 1893

(Twenty years later)

September 25, 1914

(Twenty-one years later)

March 1915

(Six months later)

Early May 1915

(Two months later)

Late May 1915

(Several weeks later)

November 21, 1916

(Six months later)

December 1917

(One year later)

July 1918

(Seven months later)

November 12, 1918

(Four months later)

Late March 1870

(Forty-eight years earlier)

February 1919

(Forty-nine years later)

January 1, 1923

(Today)

April 16, 1865

(Fifty-eight years earlier)

Spring, 1864

(One year earlier)

January 1, 1923

(Today)

JANUARY 1, 1923

Tata, Hungary

Weak winter light slants through the frosted window. So another year begins. This tale of my life drones on—I have lost the thread. I have been searching the flames of our small fire, but they offer no clues. The critics have told the world that I am depressed, as if this were my personal problem. They should be more observant—everyone is depressed now. How could we fail to be? They have gone to war again and this time it has been the entire world—rulers with their reasons seizing what does not belong to them, soldiers destroying millions upon millions of lives that do not belong to them. These are the facts, and I am a realist. Interpretations get confusing.

&nbs

p; In the corner of this parlor stands the painting of a soldier and his horse, which I have been struggling to finish since last summer. The horse is good, I think. I sketched him from a stallion that lives here in a pasture of what was once my husband Ferenc’s ancestral estate. He is a deep-black Nonius, muscular with a prominent bone structure. I am told that the Hungarian army rode many of this breed during the war. This noble creature has survived his battles and is taking a rest now, occasionally being used for light farmwork. I like to visit him, to watch him canter through the quiet, open pasture, to feed him a crab apple from my hand. I have named him Obsidian, and it was he who inspired the painting. He is still strong and alert, and watched me with interest as I sketched him, which has allowed me to capture his head in a forward position. Since I studied with Emile Van Marcke in Paris, I have enjoyed portraying animals that meet the viewer’s gaze and seem to be walking out of the painting, into the third dimension. In this painting, we view both horse and soldier closely as they walk toward us side by side. The battle is just over. The horse is not wounded, but is lathered with sweat. His eyes retain the overly excited, almost wild look an intelligent animal can express when under extreme stress. His posture is tense as he walks away from the danger he has just braved out of loyalty to his master. Yes, I think the horse is good.

It is the soldier who is the problem. I have no relationship with this particular soldier, but he repels me. He wears the uniform of the Hungarian army, which means that he has fought to protect my husband’s homeland, the country that has received me in exile, but has he? He has almost certainly been conscripted to fight, as it is said that nine million Hungarians were. If this is so, he has not chosen either good or evil, but has simply done what he was told, and his is not a position with which I am sympathetic. On the other hand, it is possible that he has enlisted out of romantic ignorance, bewitched by the glamor of uniforms and weaponry, the reassurance of comrades and marching music, the dream of glory. Such a young soldier, though he is tragically mistaken, could be sincere. Do we not all want to become more than what we are? But then again, I tell myself, he may be not only naïve, but twisted in his heart, not caring that he kills, even liking to kill. People are complex creatures, and soldiers, I think, are no exception.

I have not been able to complete the face of the soldier because I do not know him as I know the horse. I do not really want to know him. I have seen too many soldiers. But I need, though I do not want, to know him. I cannot paint what I do not understand, and I need to paint this soldier who is every soldier. If I can know him well enough to paint him, perhaps I will understand.

I do not try to understand the causes and effects of this war, or any war, the way my husband and his friends continually try to do. I leave it to others to analyze political issues. I paint people and animals, and it is they I try to understand. The people who have engineered the conflict appear to me to have simple, hateful motives—greed, pride, anger. I do not want to paint them. The soldiers’ motives are much more elusive. Their job is to kill and to be killed, but I do not know why they would agree to such a job, and I do not think most of them know, either.

The city of Tata has erected a memorial in the square, engraving on the granite base the names of hundreds from this small community alone who have perished. Their mothers, wives, and children visit the monument to honor their loved ones, to keep them in memory, but I do not think they understand what has happened. I have seen them standing there speechless, their hands hanging helplessly at their sides, looking up with blank faces at the monument, a bronze of a young soldier. If he had been sculpted differently, he might immortalize the flesh and breath of men they have lost, but the sculpture fails to inspire. He is not standing to proclaim a noble victory. Instead he has fallen and lies on the ground, raising only head and torso, as if with his last strength, to lift a bugle to his lips—a message to those who study war?

If only I could talk with Papa, I might be able to understand.

JUNE 1864

(SIXTY-ONE YEARS EARLIER)

Franklin, Tennessee

Papa is preparing the wood for a piano. I stand behind him on tiptoes, watching as he smooths the surface with his plane, the muscles in his back standing up like ropes from the effort. Papa is a slim, strong man with light-brown hair that curls around his neck and ears. Its gold and red streaks catch the sun. He is the center of my world, and whatever I do during the day, I keep returning to him. When he looks up at me, light shines from the blueness of his eyes and we don’t need to say anything because I know he loves me and I love him.

Papa is an artist, a master woodworker. He says he is fortunate to work with his body as well as his heart. He says an artist is someone who shows people the beauty that is all around us, beauty they might not have noticed. I always see beauty when I am with Papa. Today he is using a new wood for a special piano. Its grain alternates gold, brown, and red, like the strands of his hair in the sun.

“Papa, what is this wood with all the colors? I have never seen it before.”

“This is rosewood, my Matilda. It is like the rosewood in our garden, but you have never seen the inside of the big branches. This is how rose branches look inside. And this is a special kind of rosewood that my customer shipped all the way from a country in South America called Brazil.”

South America. Brazil. I ponder the sounds of the unfamiliar names. I am used to Papa talking about places of which I have no knowledge—Saxony where he was raised, New Orleans where he immigrated after finishing the training in his guild. The farthest I have travelled from Franklin, Tennessee, is to the neighboring towns where he takes me on rare occasions to deliver furniture. Once we travelled as far as Nashville, a city so large and busy I remember it only as impressions of tall buildings, rattling carriages, and strange new smells all mixed together. I am content in the small, secure world of our family home, and as yet I have no desire to wander.

Papa lays down his plane, takes my tiny hand in his large, work-roughened hand, and strokes it across the satiny surface of the wood. It feels like the wondrous black walnut bannister of our staircase, a single piece of wood that Papa has made to curve and turn all the way from the first floor of our house to the second. The bannister wood feels like it is still alive because it holds heat or cold from the air. Today, in the late morning sun, the rosewood is warmer than my hand. I stroke it, and then stroke Papa’s soft brown beard.

“Shall I sand the wood now, Tillie? What do you say?”

I nod, and soon a delicious fragrance arises. Struck by a new idea, I run to the garden to smell first one rose and then another, each variety similar to yet unique from the others, as I have long known. Now I marvel that the wood scent is like them all in sweetness but unlike them because it is richer and deeper. I break off a stem from a bush of hearty red roses and inhale—yes, something like Papa’s wood.

As I loved to do then, I take the stick and trace in the dry soil, outlining, erasing, outlining again the images of a bloom, a woody stem, a piece of cut wood, a rosewood piano.

I do not yet have the words, but that morning just a few months before the battle, I sense, more deeply than thoughts or words, how all living things belong to each other. This is what I will always want to draw.

*****

JANUARY 1, 1923

Tata, Hungary

But however will I draw this soldier as belonging to all of us? I do not know how to bring this grieving to its conclusion.

My parents’ sober, noble faces watch me from the miniatures on our mantelpiece, challenging me to recover from tragedy and disaster as they always did.

Nearly sixty years ago, just after the Civil War battle that changed the course of our family’s lives, Papa entered the devastated hallway of the home that he had built with his own hands. He clutched the box of precious woodworking tools he had managed to save from the pillage of our property, the pillage that our enemies required for the purpose of killing our neighbors. He surveyed the scene in silence, a

nd bowed his head for a long moment. When he raised it again, he told us, “We have our lives. We have each other. Now we will rebuild.”

Was he not angry over all the life and beauty they took from us, all that could never be recovered? I did not have the words to ask him then—their war had literally stolen my voice and it was months before I could find it again. I could not tell him how I hated them. I could not remind him that they had even stolen some of us from each other.

Mama used to have a ruby and gold vase that she had brought to Tennessee all the way from Bavaria. The year before the battle, when I was five years old, I was holding the faceted crystal to a candle flame, turning it this way and that as it split the light into hundreds of pieces and cast it across the dining room walls. Suddenly the precious object slipped from my hands and shattered at my feet.

“Mama! Your treasure!” I cried. If it had been my favorite porcelain doll lying at my feet in pieces, I would not have been more upset.

Mama took my face between her warm, strong hands and smiled with her eyes. “Hush, little one. It is only a thing. You are the treasure, Matilda.”

Then she was weeping, and left the room. Papa lifted me to his knee.

“Your Mama is not upset about the broken vase, Tillie. She has lost two of her true treasures, Julian and Julia.”

Earlier that year, my two-year-old twin brother and sister had run from the backyard to the stream in the woods and drunk the water. When Mama reached them, they were holding their stomachs and vomiting. Union soldiers had poisoned the stream in anticipation of a battle, but there was no battle in Franklin, Tennessee, that year. There were only two dead babies laid out on our dining table like perfect porcelain dolls.

*****

DECEMBER 3, 1864

(SIXTY YEARS EARLIER)

Franklin, TN

We are in the Carters’ parlor for Tod Carter’s funeral. It feels so different from the room of our last visit here only weeks ago. The drawn curtains enclose us in a dark sadness. Black cloths cover the mirrors, silencing everyone. In the middle of the room, Tod’s body lies on a table with some holly laid around him. It is frighteningly still.

Last night, Papa explained what happened. Tod died yesterday from wounds he received in the battle two days before. At first the family couldn’t find him and went out to search the terrible fields of death. His sisters found him badly wounded—the rest of the family knew by their screams that they had found him. Some soldiers carried him into his house, wrapped in an overcoat. Dr. Roberts came to take care of him, but there wasn’t much he could do. They knew he was going to die, though he was able to talk with his family for a while first. They were able to say good-bye.

Lift My Eyes

Lift My Eyes